Tell us a little bit about your new collection: what’s the significance of the title? are there over-arching themes? what was the process of assembling it? Is it a project book? etc.

I’m the father of three neurodiverse kids and the work in The Boy in the Labyrinth is a conversation about my navigation through a number of pivotal experiences through the allusion of the Theseus and the Minotaur myth. Thematically, the work contends with failure—namely my failures as a neurotypical parent unable to see beyond my own vantage point and it’s also about the precarious position of vantage point.

I started crafting the work when my first son was born and diagnosed with autism. It had started out as a suite of “The Boy in the Labyrinth” poems that evolved into a mosaic of prose collages. Eventually I realized that the vantage point I had drafted as a neurotypical dad was problematic . . . ablest. So I crafted poems around the vantage point to critique myself.

I don’t have a problem calling any unified work a project—sometimes the term is seen with suspicion, but I think it honestly captures the way I write. I like to nest with my obsessions, exploring all the different possibilities and angles, before I release the work.

The Boy in the Labyrinth interacts with the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur at the center of the labyrinth. They also reference algebra and math problems: can you tell us a bit about the influence of mythology on your work? How about math?

My eldest son is really adept at causal analysis. He thinks mathematically and because much of the work was drafted while I was caring for him, his way of thinking influenced the course of my explorations. Where he struggles is often where I struggle, and that’s with figuring out human motives. I think myth is useful for attempting to understand human motives—even though sometimes the outcomes can be surprising.

In the end, I was interested in the basic goals of algebra—solving for X—and also the basic goals of the parable—to instruct. I saw that the two ideas could collaborate to create both understanding and mystery.

Which writers (living or dead) do you feel have influenced you the most? Are these influences apparent in your new collection?

My earliest poetic influence was the work of Galway Kinnell and Sharon Olds. My first creative writing teacher introduced me to their works when I was an undergraduate. I then branched out and sought work by Asian American poets. That’s when I discovered Li-Young Lee, Marilyn Chin, and Garrett Hongo.

I think you see more of Kinnell in this particular work than the other folks. I’m thinking, particularly, about Kinnell’s The Book of Nightmares, which is a long poem that is often about his son. I mostly see later influences like Killarney Clary and Allison Benis White’s Self-Portrait with Crayon as well as some of the work of David Welch who was the initial influence after a poetry festival I had attended in Alabama. But the broader slate of influences for the book is big. I read DJ Salvaresse’s work online as well as his father, Ralph’s book. I also read Neurotribes by Steve Silberman that affected the later direction of the work.

This is your fifth book; how does it feel different (or similar) to your other books? In process or in content?

I think, going into the book, I was a little frightened. Because it was nakedly about parenting and circuitously about my kids, I was worried about doing harm. I’m still worried, frankly. My fear has always been in the fixing of a particular moment in my children’s memory which they may return to and which may later affect them. So that was the journey with this particular book. It was and is a hard book for me to write and to process.

What are you working on now that your book is out in the world?

I’m working concurrently on two projects. I am writing a series of broken sonnets called “Diaspora Sonnets” that negotiate with my family’s narrative of immigration back in the 70’s. I’m also writing a series of ekphrastic and journalistic pieces called “Nocturnes” which explore war, atrocity, and the camera.

What art, writing, or media is moving you right now?

Strangely, I’m consuming silly YouTube clips by people on The Voice. Particularly the anonymous turns. Meredith, my wife, thinks that I’m ridiculous for watching them, but I love them because they’re inherently hopeful and there’s constantly, constantly, the moment of the miraculous. Yes, I now they’re completely formulaic, but they make me cry with joy.

Sample poem from The Boy in the Labyrinth:

Autism Screening Questionnaire — Speech and Language Delay

1. Did your child lose acquired speech?

A fount and then silence. A none. An ellipse

between–his breath through

the seams of our windows. Whistle

of days. Impossible bowl of a mouth–

the open cupboard, vowels

rounded up and swept under the rug.

2. Does your child produce unusual noises or infantile squeals?

He’d coo and we’d coo back. The sound

passed back and forth between us like a ball.

Or later, an astral voice. Some vibrato

under the surface of us. The burst upon–

burn of strings rubbed

in a flourish. His exhausted face.

3. Is your child’s voice louder than required?

In an enclosure or a cave it is difficult to gauge

one’s volume. The proscenium of the world.

All the rooms we speak of are dark places. Because

he cannot see his mouth, he cannot imagine

the sound that comes out.

4. Does your child speak frequent gibberish or jargon?

To my ears it is a language. Every sound

a system: the sound for dog or boy. The moan

in his throat for water–that of a man with thirst.

The dilapidated ladder that makes a sentence

a sentence. This plosive is a verb. This liquid

a want. We make symbols of his noise.

5. Does your child have difficulty understanding basic things (“just can’t get it”)?

Against the backdrop of the tree he looks so small.

6. Does your child pull you around when he wants something?

By the sleeve. By the shirttail. His light touch

hopscotching against my skin like sparrows.

An insistence muscled and muscled again.

7. Does your child have difficulty expressing his needs or desires using gestures?

Red faced in the kitchen and in the bedroom

and the yellow light touches his eyes

which are open but not there. His eyes

rest in their narrow boat dream and the canals

are wide dividing this side from this side.

8. Is there no spontaneous initiation of speech or communication from your child?

When called he eases out of his body.

His god is not our words nor is it

the words from his lips. It is entirely body.

So when he comes to us and looks we know

there are beyond us impossible cylinders

where meaning lives.

9. Does your child repeat heard words, parts of words, or TV commercials?

The mind circles the mind in the arena, far in–far in

where the consonants touch and where the round

chorus flaunts its iambs in a metronomic trot. Humming

to himself in warm and jugular songs.

10. Does your child use repetitive language (same word or phrase over and over)?

A pocket in his brain worries its ball of lint.

A word clicks into its groove and stammers

along its track, Dopplering like a car with its windows

rolled down and the one top hit of the summer

angles its way into his brain.

11. Does your child have difficulty sustaining a conversation?

We could be anywhere, then the navel of the red moon

drops its fruit. His world. This stained world drips its honey

into our mouths. Our words stolen from his malingering afternoon.

12. Does your child use monotonous speech or wrong pausing?

When the air is true and simple, we can watch him tremble

for an hour, plucking his meaning from a handful of utterances

and then ascend into the terrible partition of speech.

13. Does your child speak the same to kids, adults, or objects (can’t differentiate)?

Because a reference needs a frame: we are mother and father

and child with a world of time to be understood. The car radio

plays its one song. The song, therefore, is important.

It must be intoned at a rigorous time. Because rigor

is important and because the self insists on constant vigils.

14. Does your child use language inappropriately (wrong words or phrases)?

Always, and he insists on the incorrect forms.

The wrong word takes every form for love–

the good tree leans into the pond,

the gray dog’s ribs show, the memory

bound to the window, and the promise of the radio

playing its song on the hour. Every wrong form

is a form which represents us in our losses,

if it takes us another world to understand.

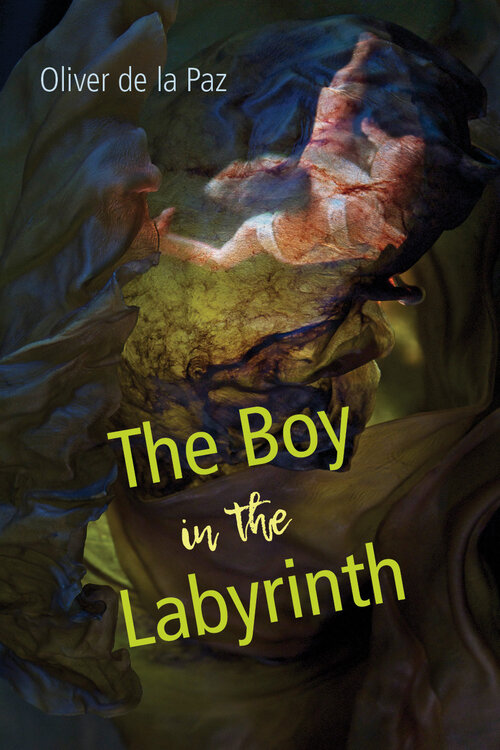

Purchase The Boy in the Labyrinth

Oliver de la Paz is the author of five collections of poetry: Names Above Houses, Furious Lullaby, Requiem for the Orchard, Post Subject: A Fable, and The Boy in the Labyrinth. He also co-edited A Face to Meet the Faces: An Anthology of Contemporary Persona Poetry. A founding member, Oliver serves as the co- chair of the Kundiman advisory board. He has received grants from the NYFA, the Artist’s Trust, the Massachusetts Cultural Council, and has been awarded two Pushcart Prizes. His work has been published or is forthcoming in journals such as Poetry, American Poetry Review, Tin House, The Southern Review, and Poetry Northwest. He teaches at the College of the Holy Cross and in the Low-Residency MFA Program at PLU.